Coming to PBS on March 18 and 19, 2024!

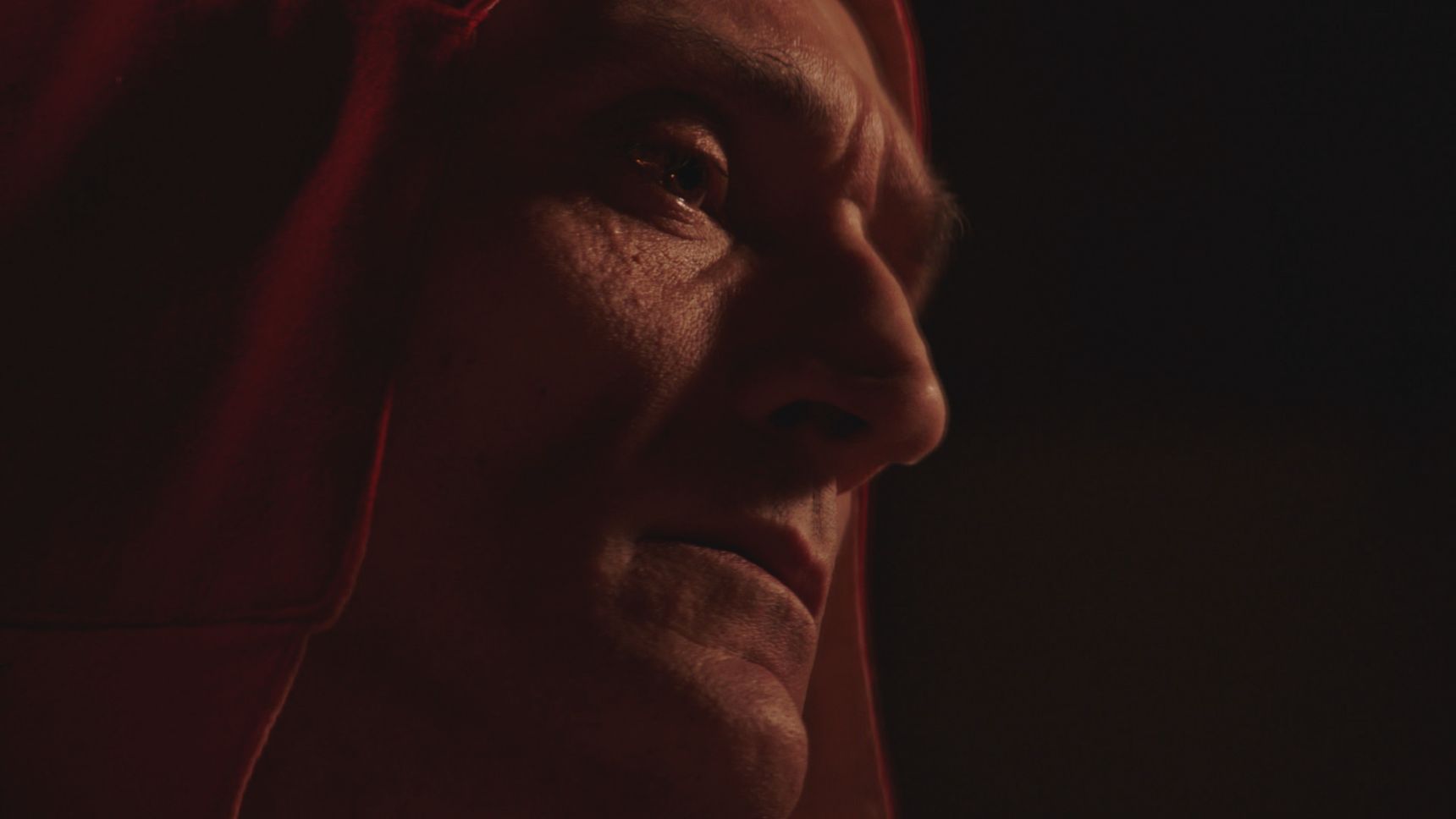

“DANTE: Inferno to Paradise, a groundbreaking two-part documentary film, presents and explores the extraordinary power, beauty and drama of Dante’s great masterwork, The Divine Comedy, set within the riveting circumstances of the poet’s own life, and of the turbulent times he lived in.

“No feature-length documentary film has ever fully exploited for an English-speaking audience the stunning power, reach and drama of Dante’s biography, or of the soaring poetic masterpiece he created – a poem that stands to this day at the very apex of world literature and culture.

“‘Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third.’ —T.S. Eliot, 1924

“DANTE will bring deep and widespread awareness of Dante’s significance and immense contribution to world culture: an impact that has reached now across 700 years with a text that speaks as powerfully to contemporary readers today as it did to the men and women of Dante’s own time. The modern-day relevance of the story of Dante’s life and work is astonishing, as people everywhere look for signs of hope and redemption and a way forward in circumstances as challenging in their own way as Dante’s own.” —ricburns.com

“DANTE: Inferno to Paradise is a two-part, four-hour documentary film chronicling the life, work and legacy of the great 14th century Florentine poet, Dante Alighieri, and his epic masterpiece, The Divine Comedy, one of the greatest achievements in the history of Western Literature. The ambition of the film, which combines powerful dramatic reenactments, colorful interviews with renowned scholars, exquisite archival material and scenic filming, is to bring to life and make accessible, to the widest possible audience, the transformative power and beauty of this singular work of art. The film is divided into two two-hour episodes. Part One: Inferno explores the historical background of medieval Florence from 1216 to Dante’s birth in 1265, and recounts the dramatic details of Dante’s childhood, education and early literary and political career, culminating in his exile in 1302, and his decision to begin The Divine Comedy in 1306 – plunging with Dante and his readers into the underworld itself where, guided by the great Roman poet, Virgil, he will meet a vast cohort of historical and mythological figures – arriving finally at the very bottom of hell, in their encounter with Lucifer himself. Part Two: Resurrection explores Dante’s experience in exile, and his completion of the last two parts of the Comedy, shortly before his death in Ravenna in 1321. Interweaving soaring scenes drawn from Purgatory and Paradise, the film goes on to explore the afterlife and literary and cultural fate of Dante’s masterpiece from the time of his death down to today.” –Steeplechase Films