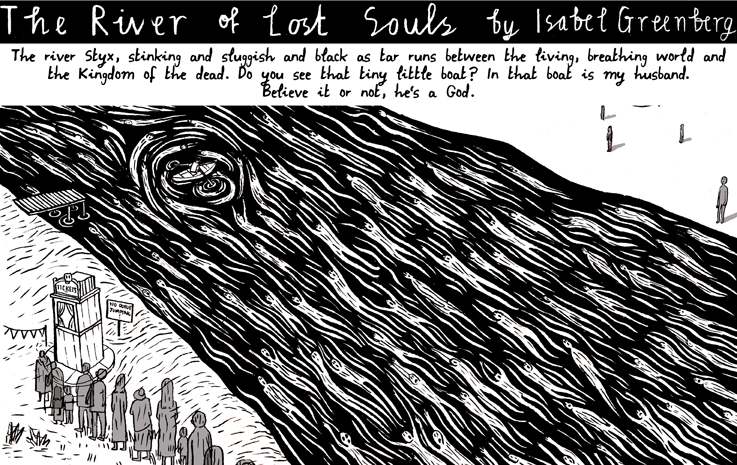

“The river Styx, stinking and sluggish and black as tar runs between the living, breathing world and the Kingdom of the dead. Do you see that tiny little boat? In that boat is my husband. Believe it or not, he’s a God.” —Isabel Greenberg, “The River of Lost Souls”

The image above is the first panel of a graphic short story produced by artist Isabel Greenberg for The Guardian in 2013. Read the full story here.