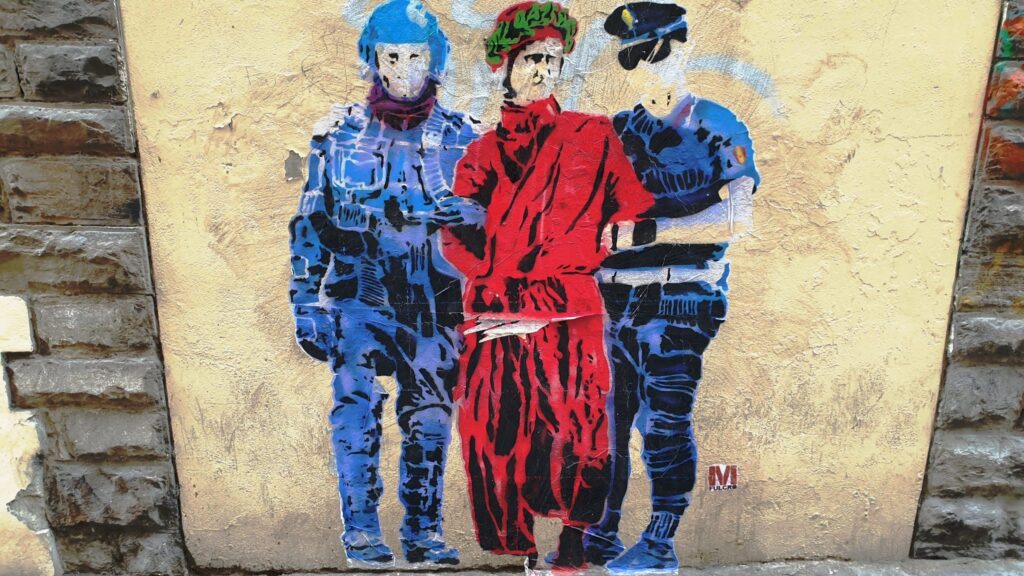

“Fantastic this work, certainly dating back to the lockdown in March [2020] and unfortunately already in an advanced stage of deterioration. Protagonist Dante Alighieri, acknowledged father of Italian literature and language, author of the Divine Comedy, dressed as always in red and crowned with laurel. Arrested as caught without a mask by a policeman with an anti-Covid 19 mask (with an American uniform?) and by another figure in a spacesuit (an astronaut?), also with a mask! Live-size pictures. Many metaphors can be ventured! Florence, via delle Seggiole.” —Arte Leonardo blog, Leonardo da Vinci Art School

Robert Schwentke, dir. R.I.P.D. (2013)

“There are many descriptions of the afterlife in fiction that can be traced back to Dante’s imaginative journeys. The wacky afterlife universe depicted in the 2013 movie R.I.P.D (Rest in Peace Department) can’t shake off the legacy.

“When a Boston police officer is killed by his renegade partner, he is immediately whizzed up to a questionable Heaven where he discovers that everyone has to answer for past crimes in the thereafter – or join R.I.P.D, Inferno’s police force. The task of the R.I.P.D is to catch ‘Deadoes’, the souls of the deceased who refuse to accept their fate and instead return to the world of the living in order to spoil it.

“The ascent to where R.I.P.D resides is a helical ride for the recently departed, a cocktail of two shots of Inferno, half a Purgatorio and one of Paradiso. Sitting under the department of ‘Eternal Affairs’, R.I.P.D is run by a chief, half Virgil, half Minos, whose role is to give the new recruit a tour of the establishment. The movie seems to suggest that if you’re not simply visiting Hell (like Dante the pilgrim), then you’re either a convict or an (infernal) law-enforcement officer, whose job is to keep the damned away from the living.

“Dante’s circles of Hell are alluded to in the prison cells of the R.I.P.D precincts and in its staff’s crammed offices. Hell is other people working in the next R.I.P.D cubicle.” –Cristian Ispir

Elizabeth Coggeshall, “Bad Apples and Sour Trees”

“Among the Times photographs, there is an image of a Black protester in Atlanta, cutting through the smoke, his open palms raised. He cries out, a vox clamantis in deserto, in righteous rage against the injustice that killed George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black Americans. His defiant approach is a picture of the words Virgil uses to describe his charge at the entrance to Purgatory: ‘He goes seeking freedom, which is so precious, as one knows who gives up his life for its sake.’

“Among the Times photographs, there is an image of a Black protester in Atlanta, cutting through the smoke, his open palms raised. He cries out, a vox clamantis in deserto, in righteous rage against the injustice that killed George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black Americans. His defiant approach is a picture of the words Virgil uses to describe his charge at the entrance to Purgatory: ‘He goes seeking freedom, which is so precious, as one knows who gives up his life for its sake.’

“The freedoms demanded by this protester — economic, legal, political, bodily — are material ones. He seeks liberation from ‘the policies that ensnare‘ Black Americans in an unjust system. These freedoms are substantially different than the immaterial freedom sought by the pilgrim in his journey up the mountain. The freedom Dante’s pilgrim seeks, like that which we seek to restore to our civic institutions, is a moral one: the freedom of moral integrity, which comes from the alignment of one’s actions with one’s principles.” —Dante Today co-editor Elizabeth Coggeshall, “Bad Apples and Sour Trees: Dante on Systemic Injustice, Rage, and Reform,” The Sundial (September 15, 2020)