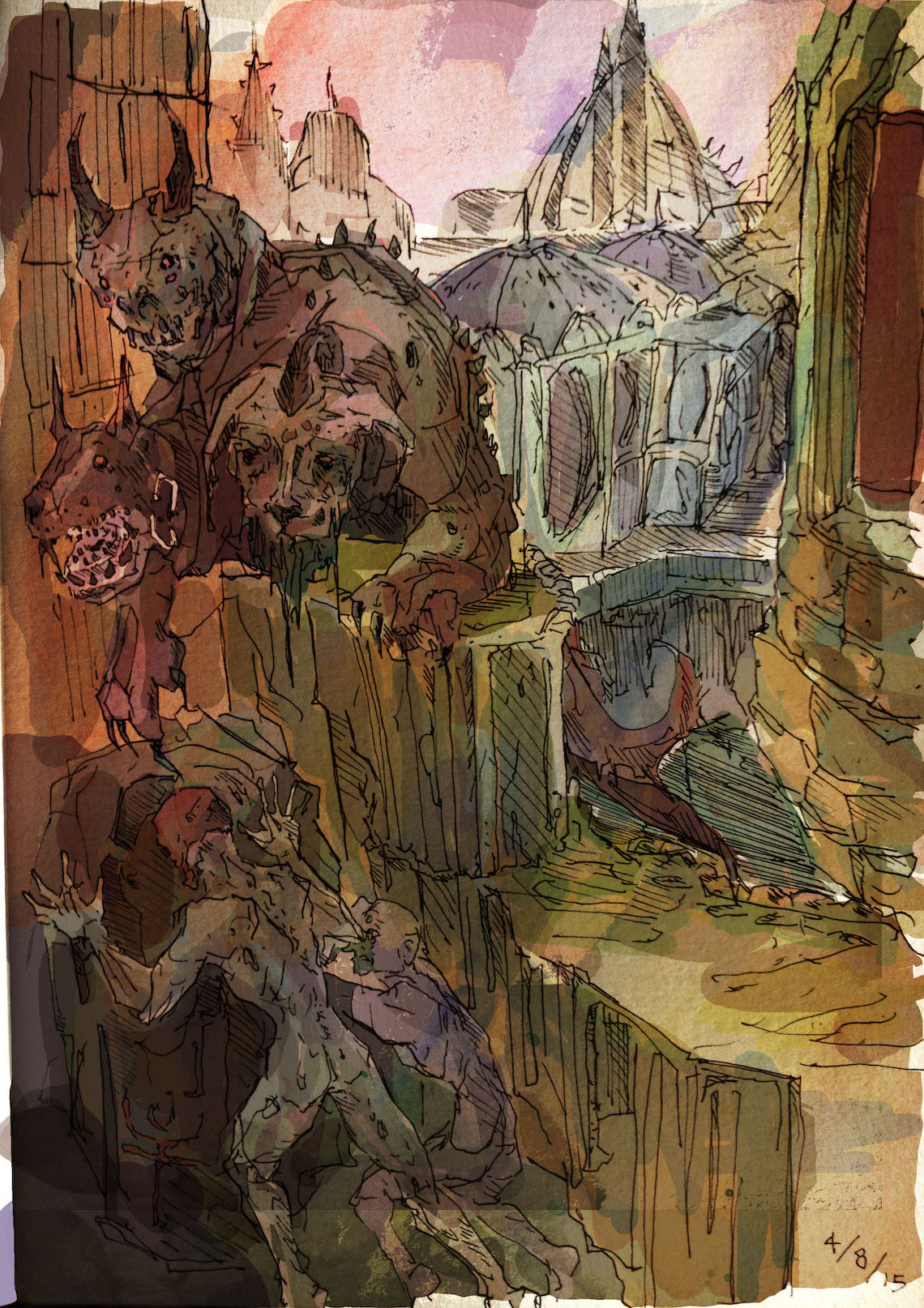

Monaramis’s depictions of Dante Alighieri’s Inferno feature an array of muted colors that stem from an earthy palette. These are layered over the black contour of the scene (which appears to have been drawn by hand). The composition focuses on Cerberus as it imposes over a historical monument, seemingly intent to sniff out the two figures hiding in the foreground. The line-work of this piece is sketchy and heavily gestural, which reinforces the dynamism of the Canto depicted. — Monaramis Art, “Dante’s Inferno— La Divina Commedia,” Behance, 2015 (Retrieved March 28, 2024).

Paul Laffoley’s Dantean Triptych (1972-1975)

“Paul Laffoley’s extraordinary triptych of Dante’s Comedy brings Dante’s ‘altro dove’ (literally, ‘other where’) into a remarkably comprehensive and vivid translation. In the history of illustrations of the Comedy, there is nothing like it. Laffoley is the only artist, as far as I know, to have depicted all one hundred cantos and the topography of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, in the same piece.

“With the classical, religious, mathematical, esoteric, and cosmo-logical themes present in Laffoley’s opus, Dante’s Comedy was a natural text for him to turn his attention. The Divine Comedy triptych, 1972-75 (plates 29, 30, and 31), indubitably bares his trademarks of architectonic precision, mind-boggling detail, immense erudition, symmetry, balance, and the word-techniques that lend themselves to an illustration of something as vast, multidimensional, intricate, and based in language and interpretation as Dante’s Comedy.” — Arielle Saiber, “Laffoley and Dante’s Other Worlds,” in The Essential Paul Laffoley, ed. Doug Walla (2016), 23-29.

Gli Scavi di Palazzo Franchetti

“Poco più di un mese sono durati i lavori di scavo per riportare alla luce i resti della casa del conte Ugolino della Gherardesca nella zona dove sorgeva il piaggione, sul Lungarno Galilei nei giardini della storia sede del Consorzio di bonifica Basso Valdarno. Le operazioni, effettuate in regime di concessione ministeriale e iniziate a metà luglio, si sono concluse come da crono-programma, venerdì 26 agosto [2016].

“Prima dell’inizio degli scavi, oltre alla tradizione di età moderna, anche la documentazione scritta medievale rintracciata da Maria Luisa Ceccarelli Lemut testimoniava che nell’area, al tempo nella cappella di San Sepolcro, erano ubicate alcune abitazioni dei della Gherardesca, la famiglia aristocratica che ebbe così tanta rilevanza non solo a Pisa ma in Toscana e in tutta l’area tirrenica e dette i natali al conte Ugolino di dantesca memoria.” — “Palazzo Franchetti, scavi ultimati: torna alla luce la casa del Conte Ugolino,” PisaToday (September 5, 2016; retrieved February 14, 2024)

“Revisiting Dante’s Florence: Experiencing Dante’s ‘circles of hell'” Essay, Sarah Odishoo (2021)

“Dante’s Florence was a circle of intrigue between the Holy Roman Catholic Church and Firenze’s powerful political parties. Dante, as a young Italian, became part of the struggle to keep the city for the people. He lost. He was exiled. He wrote The Divine Comedy, starting with The Inferno. Mirroring through reflection.

“Dante’s Florence was a circle of intrigue between the Holy Roman Catholic Church and Firenze’s powerful political parties. Dante, as a young Italian, became part of the struggle to keep the city for the people. He lost. He was exiled. He wrote The Divine Comedy, starting with The Inferno. Mirroring through reflection.

“I begin to understand the infernal map Dante had drawn. Florence itself is the paradigm for the nine circles of the inferno. The city is ringed around by streets that all move toward its center. In the time of Dante, the city had been a series of expanding fortresses, enlarging as the population and wealth increased. But the structure — the ringed city — with its quarters defined and stationary, is still in place. And the Arno River is one of its boundaries. Dante used Florence to define the parameters and structure of Hell — a spiraling atlas of infernal distances.

“Dante’s cosmos is just that: What one does is immediately mirrored in life and in death. As are Beatrice’s thoughts and actions; her awareness brought her closer to that state of unconditional awareness, one that sees more of the whole, the holy. The creatures in the inferno fell in love with the lesser good — money, food, fame, a lover —and staying loyal to that lesser love brings the limitations, the fragmentation of the whole. The lesser holds the whole, but the lesser is unable in its separateness from the whole to maintain the weight of all that is.” [. . .] –Sarah Odishoo, The Smart Set, August 22, 2021 (retrieved April 12, 2022)

Read Odishoo’s full essay about her journey to and within Florence here.

Dante in the British Library: Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven

On September 14, 2021, the British Library in London hosted an online event titled “Dante in the British Library: Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven”. The event featured two lectures on Dante about the following:

“Alessandro Scafi – Mapping Paradise in the Middle Ages: Dante and the Garden of Eden

“Christian scholars and map-makers of the late Middle Ages were dedicated to the search for the Garden of Eden, as described in Genesis. Could paradise be found on a map? Dante’s knowledge of geographical lore was deep, rich, and varied, and his Divine Comedy echoes contemporary debates about the location and the mapping of paradise.

“Elisabeth Trischler – Architecture and the Afterlife: How the Urban Spaces of Medieval Florence inspired Dante’s Divine Comedy

“The city of Florence underwent a significant building boom in the 13th and 14th centuries, and this expansion offers a way to explore Dante’s world. This lecture uses illustrations of the Divine Comedy from the British Library’s collection to show how Dante’s masterpiece was shaped by Florence’s urban spaces.” [. . .] —The British Library (retrieved April 11, 2022)

View the event’s listing on the British Library’s website here.