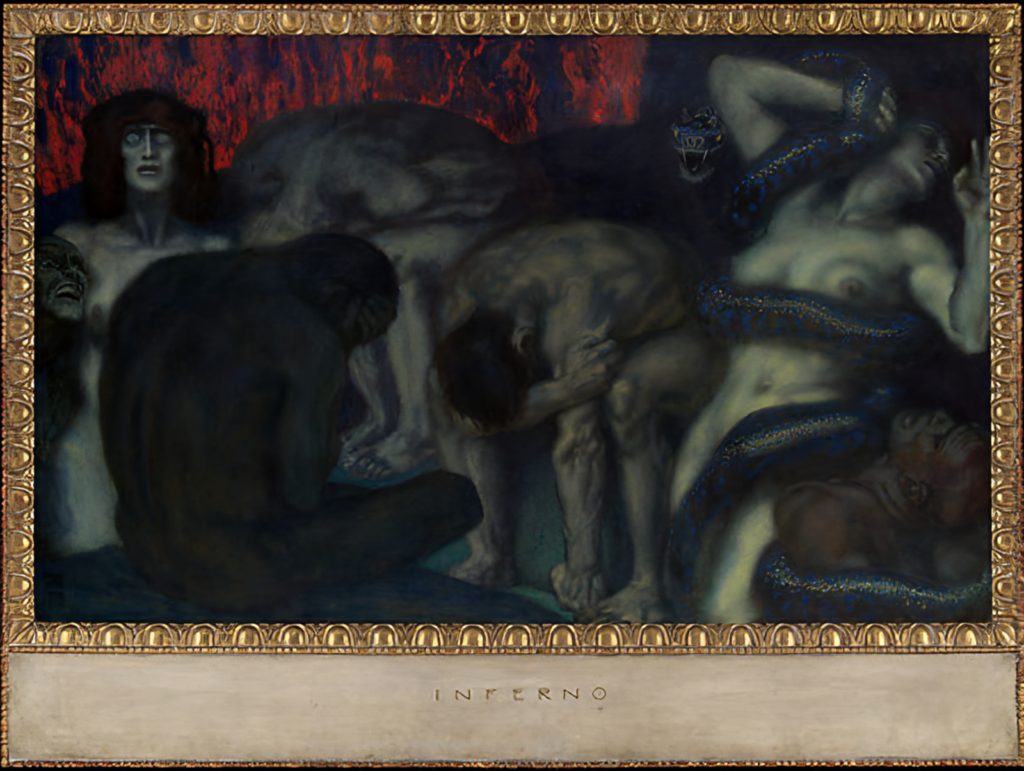

“This painting’s title refers to Dante Alighieri’s medieval epic of a journey through hell. Although Stuck employed traditional symbols of the underworld—a snake, a demon, and a flaming pit—the dissonant colors and stylized, exaggerated poses are strikingly modern. He designed the complementary frame. Stuck’s imagery was likely inspired by Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell, particularly the figure of The Thinker (see related works nearby). When Inferno debuted in an exhibition of contemporary German art at The Met in 1909, critics praised its ‘sovereign brutality.’ The picture bolstered Stuck’s reputation as a visionary artist unafraid to explore the dark side of the psyche.” —Franz von Stuck, Inferno, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1908 (retrieved February 28, 2024)