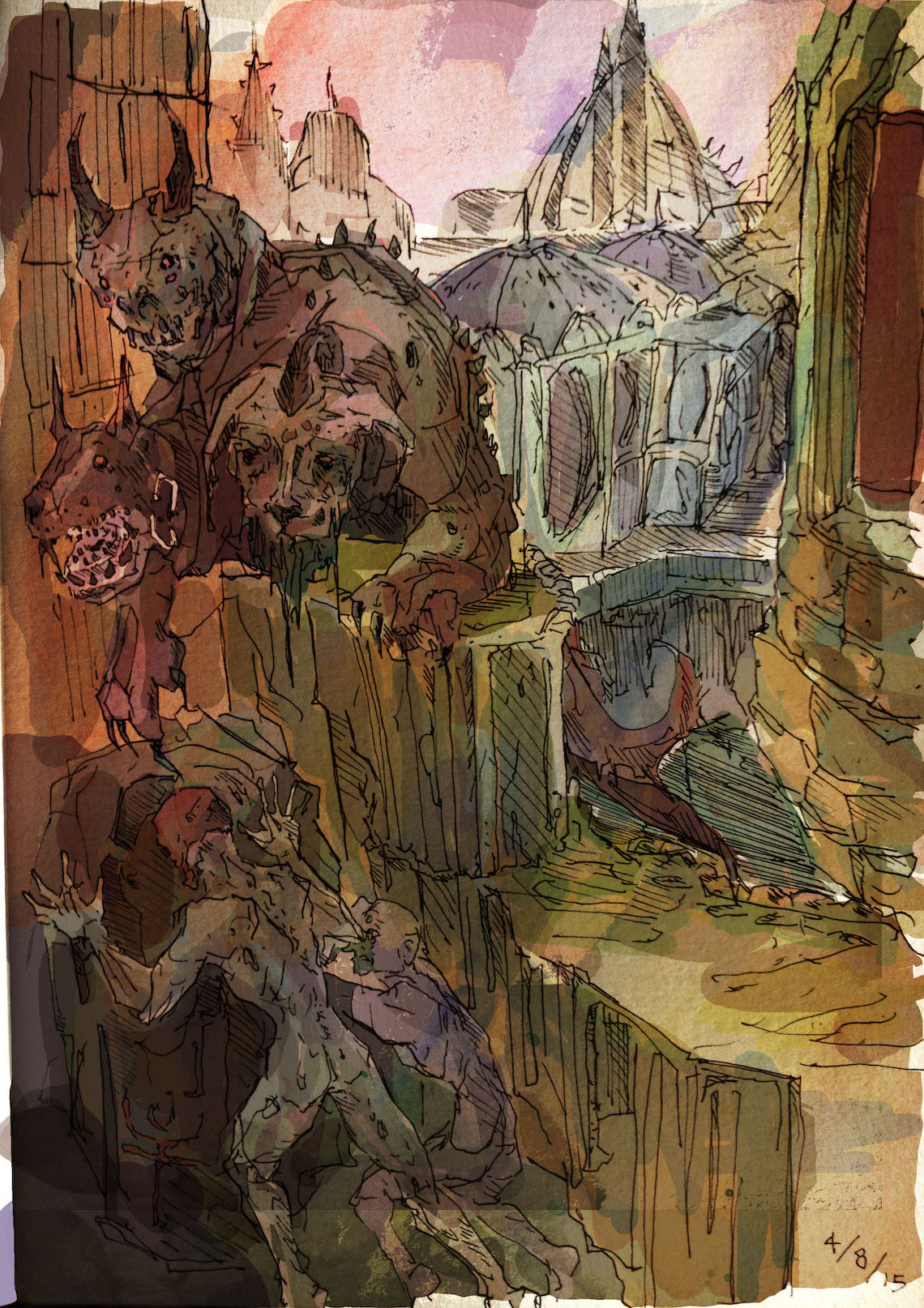

Monaramis’s depictions of Dante Alighieri’s Inferno feature an array of muted colors that stem from an earthy palette. These are layered over the black contour of the scene (which appears to have been drawn by hand). The composition focuses on Cerberus as it imposes over a historical monument, seemingly intent to sniff out the two figures hiding in the foreground. The line-work of this piece is sketchy and heavily gestural, which reinforces the dynamism of the Canto depicted. — Monaramis Art, “Dante’s Inferno— La Divina Commedia,” Behance, 2015 (Retrieved March 28, 2024).

Amos Nattini’s Illustrations of The Divine Comedy (1900s)

“Many artists have interpreted Dante’s afterlife by letting themselves be inspired by the culture and fears of their time. Amos Nattini, between 1915 and 1939, undertakes this great project with passion and dedication, giving us an absolutely human and realistic version of it. His lithographs were published together with the Divine Comedy text in three volumes. The edition of the Cariparma Foundation is dated 1939.” — “Amos Nattini and The Divine Comedy,” Google Arts and Culture, 1900s (Retrieved March 28, 2024).

Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s Paolo and Francesca (1910s)

German artist Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881-1919) created a depiction of Paolo Malatesta and Francesca Da Rimini, two real-life individuals featured in Dante’s Inferno for engaging in an adulterous relationship. The artist, using drypoint, depicts the affection of the two forbidden lovers in a sketchy and gestural manner that is enriched by the stark, geometrical line-work. — Wilhelm Lehmbruck, “Paolo and Francesca,” Princeton University Art Museum, 1910s (Retrieved March 28, 2024).

…and Thence We Came Forth To See Again The Stars, Group Exhibition

“The Flat-Massimo Carasi gallery reopens its doors to the public, after the protracted closure due to Covid 19, with a collective that look forward for a restart. Convinced that the physical space of the gallery will resist the broadsides of innovations and will remain an essential point of meeting and sharing with the public, we recognize that no man / woman is an island even in its own solitude (a very crowded solitude). Art, in all its disciplines, remains the most enthralling mystery and witnessing its representations in first person will simply remain of VITAL importance. We identify the works of art with the stars, to which Dante refers and illuminate the dark, so in this context we have chosen for the end of the season program, a roundup of works that would like to shape a physiognomy of contemporary being with her/his passions and obsessions, between damnation and holiness, bewilderment and hope.These are works that refer to woman/man but do not portray her/him directly. Instead they evoke his presence by interpreting the fetishes that are left behind as traces. The invited artists, using new and traditional media, adopt the most varied techniques to grasp the human dimension with sometimes simple, or sometimes, categorical gestures.” —Stefano Caimi, Michael Johansson, Guillaume Linard Osorio, Sali Muller, Jack Otway, Michelangelo Penso, Leonardo Ulian, …and Thence We Came Forth To See Again The Stars, Leonard Oulian, June 11-September 4, 2020 (retrieved on March 28, 2024)

Love, Watercolor by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1880s)

“This watercolour is inscribed with a line from the Commedia (The Divine Comedy) by the Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321): ‘L’amor che muove il sole e l’altre stelle’ (The love that moves the sun and other stars’). It is a highly finished design for a large needlework panel, but now it is considered to be a great watercolour in its own right. Burne-Jones (1833-1898) made several such designs, some of which were worked up into tapestry or needlework by the young Frances Graham, with whom Burne-Jones later fell in love.

[. . .]

“At the time of this painting, Burne-Jones was also working on his famous King Cophetua and the Beggar-maid. The model for the beggar-maid was Frances Graham, and Burne-Jones had fallen in love with her. In 1883, to his great dismay, she announced her impending marriage, and he painted in anenomes – the symbol of rejected love and death – around the figure of the beggar-maid. Here too, in Love, the colours of anemones predominate, rich scarlets and purples against cobalt and turquoise. Just as Dante lost his beloved Beatrice, and Rossetti his Lizzie, so Burne-Jones, on more than one occasion, lost his heart to those like Frances who were unable to return his love.” —Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Love, Victoria & Albert Museum Collections, 1880s (retrieved March 26, 2024)

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 92

- Next Page »